Open data is often described in terms of metadata, specifications, and formats. But for many decision-makers, it remains abstract: what real value can it create?

In the Swedish region of Skaraborg, that question was answered in a very tangible way when fifteen municipalities joined forces to tackle a shared challenge – collecting and publishing information about available plots of land.

The result was an open mapping service that makes it easier for residents to find available lots, for investors to plan new projects, and for municipalities to collaborate more efficiently. Most importantly, it became a breakthrough in showing how open data can be both understandable and useful in practice. Two key people in the initiative were Hanna Asp, Urban Development Strategist at the Skaraborg Association of Local Authorities, and Tomas Monsén, Digitalization Developer at Skara Municipality.

Do you want to read this text in Swedish? Click here!

“Tomas led the technical side, engaging with GIS and urban planning staff across the fifteen municipalities to ensure the data was shared in the right format. I coordinated the project together with Fredrik Edholm, and worked closely with urban development directors and Business Region Skaraborg to move things forward,” says Hanna Asp.

A Map That Made the Value Clear

To get the collaboration off the ground, the Skaraborg Association took a pragmatic approach – start with a prototype. A few municipalities shared their data, and soon the first version of the map was ready. The reaction came faster than anyone expected.

“About a minute after showing the prototype, one of the urban development directors – whose municipality wasn’t part of it – said, ‘Why aren’t we in this?’” recalls Tomas Monsén.

What had been difficult to explain in technical terms suddenly became obvious. A map of available plots was something both politicians and staff could instantly grasp.

“For years I tried to spark interest in open data by talking about specifications and technical benefits. It often stayed abstract. But when we could demonstrate a concrete service, it clicked,” says Tomas.

He sums it up simply: it’s the usefulness that convinces people – not the technology itself.

Confidence Through a National Standard

Publishing data isn’t always straightforward. Questions often arise: Are we allowed to share this? Are we following GDPR? Are we sure we’re doing it right? That uncertainty can easily slow things down – or stop progress entirely.

In Skaraborg, the solution was to rely on an already established national standard for land data.

“This isn’t something we came up with ourselves. It’s based on a national standard, which gives everyone confidence that we’re doing it right,” explains Hanna Asp.

That shared foundation made a real difference. When everyone used the same specification, hesitation disappeared. Discussions that could have dragged on were easily resolved: this is how we do it in Sweden. Standardization created not only consistency, but also the confidence – and courage – to publish.

Shared Platform as an Enabler

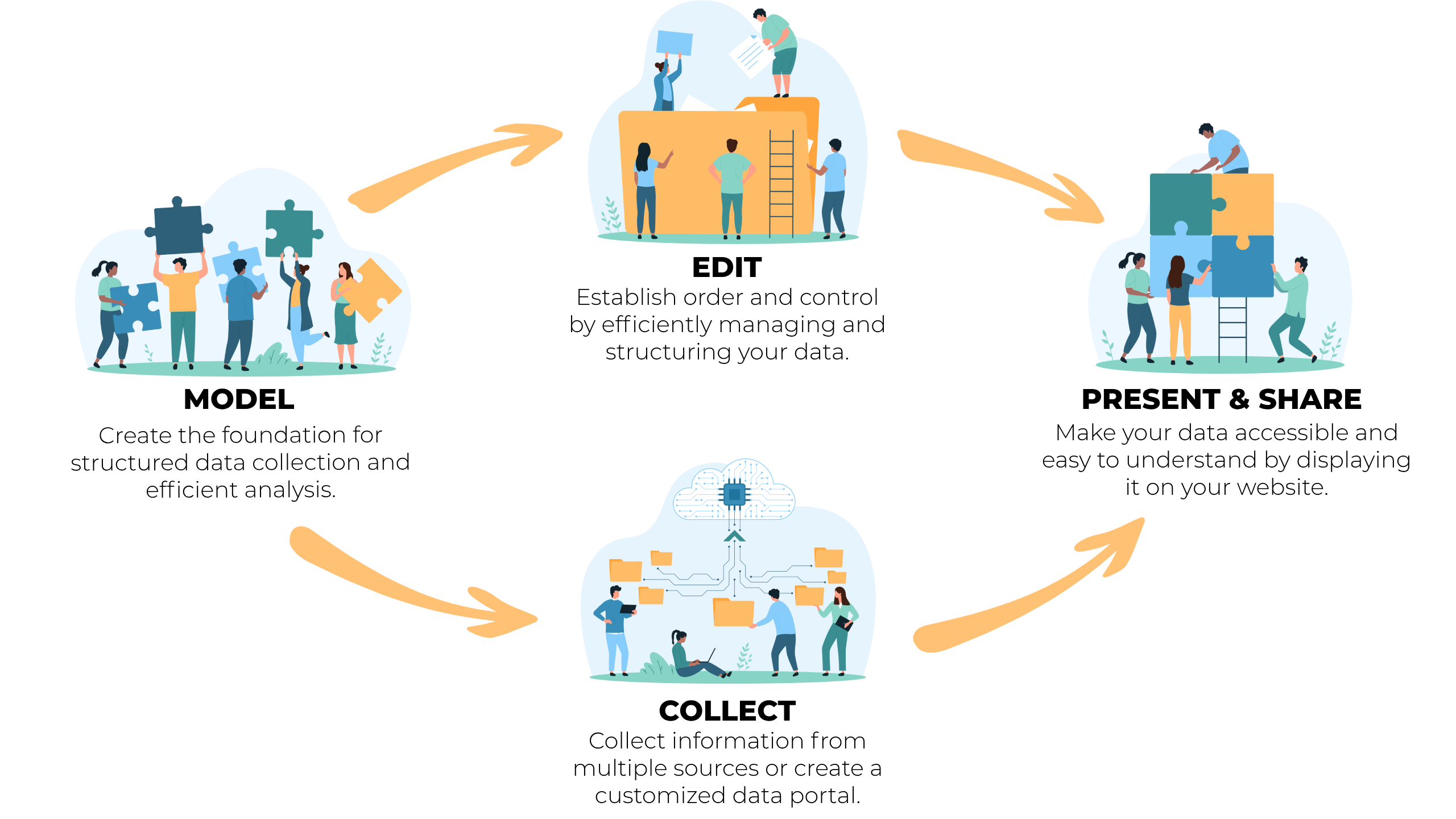

Beyond the strong tradition of collaboration in the region, another key success factor was the use of a shared technical platform. Almost all municipalities in Skaraborg were already using EntryScape, which meant they could start working together without major investments or lengthy preparations.

“All but two municipalities were already on EntryScape. For those who had it up and running, it was basically just a matter of adding their data,” says Tomas.

Municipalities that didn’t yet have the platform received onboarding from scratch, ensuring that all fifteen could participate on equal terms. But the real benefit was more than convenience. Because EntryScape is built to follow national specifications, the data was published correctly from the start – structured, searchable, and comparable across municipal borders.

Try EntryScape Free? Click here!

The result was a service that’s both user-friendly and sustainable. Residents can quickly find available plots, investors get a clear overview, and municipalities avoid building separate, incompatible systems.

“This isn’t just a map. It’s an example of what happens when you share structure, resources, and goals – and build digital infrastructure that lasts,” says Hanna Asp.

“My hope is that we can continue developing from here and show that open data isn’t a one-time effort, but a long-term way to build digital infrastructure that benefits both citizens and municipalities,” concludes Tomas Monsén.